How’d They Do That?

In a recent issue of Layers magazine, we asked readers to submit their favorite print, Web, and video designs currently in the marketplace. In turn, we promised to track down the original creators and force them to tell us their secrets (as it turns out, all we had to do was ask politely—everyone we spoke to was very nice and accommodating).

Anyway, after going through all the submissions, there were two that really captured our attention: the GE Smart Grid Augmented Reality (AR) website and the Black Day to Freedom video by Rob Chiu. In fact, we asked so many interview questions about these two projects that we ran out of room for any of the print submissions. But don’t worry, we’ve sent all the print submissions to Corey and RC over at Layers TV and have asked them to cover “How’d They Do That?” in a future episode. So after you read this article, be sure to keep an eye out on www.layersmagazine.com/layers-tv.

CHANGING YOUR REALITY

AR will have you seeing things in a different way

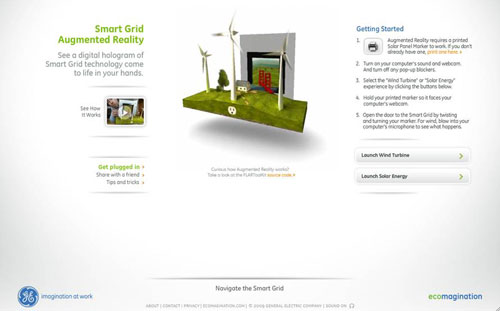

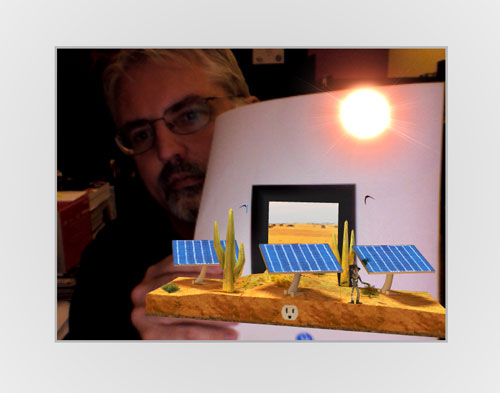

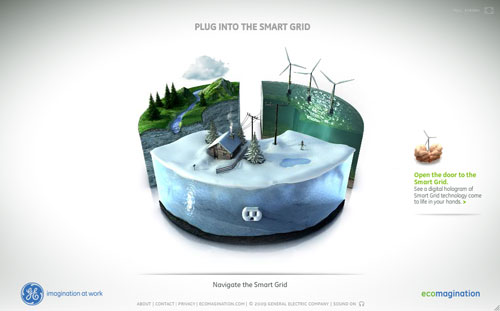

When the GE Smart Grid Augmented Reality website was brought to our attention, our productivity took a major hit for a good 25–30 minutes. If you haven’t seen AR in action, then you’ll have to check this one out for yourself. So before you read any further, launch your Web browser and head on over to http://ge.ecomagination.com/smartgrid/#/augmented_reality. Follow the instructions for Getting Started on the right side of the screen, because you’ll first need to print a page to use for the demonstration and you’ll need a webcam. Don’t worry, take your time. You’ll find that magazine pages can be very patient.

(What’s taking you so long?)

Oh, there you are. Welcome back. Pretty mind-blowing stuff, eh? AR has actually been around for some time now, but it’s a technology that hasn’t quite made it into the mainstream yet, so it’s still new to a lot of people. But as we were working on the story, AR seemed to be popping up in the news everywhere we turned.

According to the GE website, they used FLARToolKit (FL for Flash and AR for augmented reality). FLARToolKit—developed by Tomohiko Koyama (a.k.a. Saqoosha) and Ryo Iizuka—is an ActionScript 3 version of ARToolKit, which is the original C version of the application. ARToolKit was originally developed 10 years ago by Hirokazu Kato, a Professor at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology in Japan, and then commercially licensed by ARToolworks (www.artoolworks.com).

Armed with this knowledge, we decided to start with ARToolworks and trace the path that AR took to end up on the GE Smart Grid website. (By the way, if you find yourself wanting to venture into the world of augmented reality, ARToolworks offers commercial licenses for both versions of the ToolKit. [You may want to link to the opensource sites]For the open source download of ARToolKit for noncommercial use, visit http://sourceforge.net/projects/artoolkit.)

In the Beginning: ARToolworks

For the first stop on our journey, we’ll speak with Mark Billinghurst from ARToolworks. Mark is one of the founders of ARToolworks and was also involved with developing ARToolKit with Hirokazu Kato when they were both at the Human Interface Technology Laboratory at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Layers: So, Mark, would you define the term “augmented reality” for us?

Mark: Augmented reality is technology that overlays computer graphics onto the real world in real time to create the illusion that three-dimensional virtual images are part of a user’s real environment. Computer scientist, Ron Azuma, says that augmented reality has three key characteristics: It combines real and virtual images; it’s interactive in real time; and the virtual images are registered in 3D.

Layers: How did the concept for augmented reality first come about and how was it developed?

Mark: Augmented reality has a long history, beginning with early experiments with head-mounted displays by Ivan Sutherland over 40 years ago. Since then a lot of interesting research has been done by the military and in university and industry laboratories—but using very expensive, specialized technology. However, in the last 10 years, AR has become cheap enough and easy enough to use that it’s getting far more widespread. A key part of this was the development of ARToolKit by Hirokazu Kato 10 years ago. That software uses computer vision to track the user’s viewpoint and overlay virtual images over live video of the real world. For the first time, this made it easy for programmers to create AR applications. Now, people can have an AR experience through their game console, personal computer, Web browser, or mobile phone, so millions of people can easily have access to the technology.

Layers: What kind of hardware and software is needed to create and view augmented reality?

Mark: To view AR content, a user needs a camera, computer processor, and display. For most people this means plugging a USB camera into their desktop or laptop computer, but other devices such as mobile phones can also be used. To create an AR experience, people can use low-level tools such as ARToolKit, in which case they’ll need to be comfortable with computer programming. However, the development of FLARToolKit means that people with Flash programming experience can build their own AR websites. Most recently, tools such as BuildAR by the HIT Lab NZ (www.hitlabnz.org/wiki/BuildAR), also based on ARToolKit, can be used by nonprogrammers to easily create AR scenes.

Layers: Where do you currently see augmented reality being used and how do you see it being used in the future?

Mark: Augmented reality has many possible applications. Currently, it’s being used as a fantastic marketing tool, and also in computer games and certain niche areas such as medical visualization and industrial manufacturing. In the future, mobile phone-based AR will become more common and used for activities such as personal navigation or location-based social networking. [See “AR Goes Mobile.”—Ed.] I think the technology also has great potential for educational applications that teach in entirely new ways.

Let There Be Flash: FLARToolKit

Now it’s time to move on to the Flash version of ARToolKit. We think this is the version that most of our readers will be interested in. As mentioned earlier, one of the developers of the FLARToolKit was Saqoosha, CTO of Katamari Inc. (http://katamari.co.jp)—a Web creative company in Japan. He also has a blog at http://saqoosha.net/en.

Layers: When did you first learn about ARToolKit, and why did you feel there was a need for a Flash version?

Saqoosha: I read an article on ARToolKit in June 2007 [http://kougaku-navi.net/ARToolKit.html]. That was my first contact with ARToolKit. The original C version of ARToolKit required you to download and install the application to experience AR. Most people don’t want to bother with a procedure like that.

But I was very interested in AR technology and intended to tell a lot of people about ARToolKit. Flash Player is widely installed, so I thought that if ARToolKit could be use on Flash Player, many people could easily experience AR.

Layers: What kind of projects have you used FLARToolKit for?

Saqoosha: My first project using FLAR was Desktop Fireworks [http://vimeo.com/1634128]. This was very experimental and a very simple example of how to use FLAR. I recently did another FLAR project for a campaign that supported the Japan National Soccer Team with messages from supporters. The messages input at the stadium fly out from the marker [http://vimeo.com/5012399].

And North Kingdom Said It Was Good: GE Smart Grid

The GE Smart Grid site was developed by North Kingdom (www.northkingdom.com), a Swedish interactive design firm founded in 2003. According to North Kingdom’s mission statement, “Our talented team of artists have a single, unified vision to push brands to new places, bringing every facet to life through interaction, imagination, and innovation—it’s what we call our design DNA.” They’ve proven this with their creative use of AR. In addition to GE, they’ve also done work for Coca-Cola, Toyota, and Vodafone. We’ll speak with one of North Kingdom’s co-founders, Roger Stighäll.

Layers: When Goodby Silverstein & Partners/GE first approached North Kingdom about the Smart Grid project, was AR already part of the grand scheme? How did the AR portion of the project progress from beginning to end?

Roger: Goodby were the ones to bring up AR as a potential ingredient for the campaign. For a long time we had been curious about AR, but never actually got our hands really into doing it. Since the field was quite unexplored to both us and Goodby, we got a couple of weeks to do R&D, to figure out what was achievable. We had a lot of fun (and certainly also frustrating times) trying to make the most out of the AR experience.

We had a very organic and open approach to the development of the AR experience. We set out with the idea that the object should come out of the marker and somehow be interactive, and then we added new features along the way. Some ideas were tested and canned, the ones you see survived. The simplicity of FLARToolKit is its main feature, so the implementation of the kit was very fast—basically the first thing we did.

Layers: How advanced does a Flash developer need to be to really take advantage of FLARToolKit?

Roger: You don’t need to be a star. It’s very simple if you have a basic understanding of 3D graphics. There are loads of very good tutorials that any AS programmers could wrap their heads around.

Layers: Does North Kingdom have any future plans for AR?

Roger: Certainly, this is a fun and eye-catching area, so we’ll continue to play with this as long as we think we can create interesting experiences in this field. We are concepting some interesting AR ideas that hopefully will come to life this fall.

AR goes mobile

Want to see some really cool AR applications for mobile? Then check out the Wikitude AR Travel Guide (www.mobilizy.com). Developed for the Android platform, this app is based on Wikipedia, Qype, and Panoramio. Through the use of AR, digital information about landscapes and landmarks is overlayed on the live view image of the cell phone.

SPRXMobile also just recently announced their first mobile AR browser at http://layar.eu. Just like Wikitude, Layar uses a combination of the phone’s camera, GPS, and compass to overlay real-time digital information on top of the mobile device’s screen. Layar can help you find ATMs, houses for sale, hotels, etc. Be sure to watch the cool video demo. Currently, this app is also only available for Android devices, but we can’t imagine that the iPhone would be too far behind now that the new iPhone 3GS has a digital compass.

Practical applications

See how BMW is putting augmented reality to work. Visit www.bmw.com/com/en/owners/service/augmented_reality_workshop_1.html and check out the demo video under Related Topics.

Some not-so-practical, but really cool, applications

If you’re a Star Trek or Transformers fan like we are, then you’ll get a kick out of these AR experiences from Total Immersion (www.t-immersion.com). You’ll probably need to install the plug-in for your browser, but it’s worth the effort.

EMOTIONS IN MOTION

How video can help us better understand our world

The Layers’ reader who recommended Rob Chiu, recommended his entire body of work, so we spent the better part of an afternoon reviewing all the pieces Rob had available at http://theronin.co.uk/Motion. From the technical beauty to the eye-catching, seamlessly integrated effects to the strong emotional impact, we found ourselves completely engaged in every single video.

Based in London, Rob has worked in the field of short film and motion design since 2000. Under the working alias of The Ronin, he has produced narrative-based works for clients such as Leica Camera, BBC, Greenpeace, EMI Records, Nokia, Channel 4, and 20th Century Fox. His short films have been featured in a number of film festivals including Edinburgh, onedotzero, RESFEST, and Clermont-Ferrand. In 2005, his three-minute, animation-based documentary on psychosis for Channel 4/APT Films won the award for best animated short in Canada. His short films Black Day to Freedom and Things Fall Apart have toured extensively as part of the festival circuit, winning numerous awards along the way.

In fact, it’s Black Day to Freedom that we’re going to focus on here. According to Rob, the film was “created as a fictional back-story to the global problem of the displacement of peoples. It portrays a city in turmoil with the loss and tragedy of a young family at the center of the tale.” After we recovered from some the very powerful imagery contained in the film, we learned that Rob animated it entirely in After Effects—he hadn’t used any 3D applications at all. It was time to ask Rob some questions.

Layers: Let’s begin with a little bit about you. You originally started out as a print designer. When did you first know that you wanted to be a filmmaker?

Rob: I’ve always wanted to tell stories whether through music, design, or film. I started in print design, as that was the easiest route back then. I was heavily influenced by the likes of David Carson, Neville Brody, and Attik and was drawn into the world of Photoshop. I naturally moved into After Effects after discovering that it was relatively similar to Photoshop with the added bonus of a Timeline. The first version I used was 3.1, so it’s going back a bit now. While I was working in a design agency, I studied for a BA degree in Graphic Design and used the course as an output for my personal work. After teaching myself the basics of After Effects, I submitted a short AE-based film as my final piece, and then used that to launch my career in moving images. I’m now slowly moving away from pure motion design and moving into live action film directing—but it basically all evolved from a love of print design.

Layers: You’re also a photographer. Does your photography play a factor in any of your productions?

Rob: Mainly, I use photography as a tool to experiment with framing, lenses, depth of field. I then take away what I’ve learned from taking stills and apply it to my film-based work. It allows me to get on the same page with a DoP [director of photography] really quickly and definitely allows me to be more confident when directing something. Secondly, I use my photography for storyboarding and style frames. When I boarded the Webbys intro, I used a series of photos that I had taken over the years as a reference for the client as to how I intended to shoot and grade the piece. Lastly, I occasionally do the odd illustration for magazines such as .net or Computer Arts and I base my designs on photographs that I take.

Layers: Can you give us a short list of the equipment that you use, including cameras and software?

Rob: It all depends on the production. I don’t own that much kit and the stuff I do own is used mainly for personal projects, as it’s not professional gear. I recently shot a short film on two RED cameras—one hand-held, the other on steadicam—but there’s no way on earth that I could afford to actually own this kind of gear. As far as my own gear, I own a couple of Macs—a MacBook Pro and an older G5 tower, which I’m soon getting rid of for a new iMac due to the space limitations at home. Cameras I have include a Canon HV20 HDV camcorder with a Letus adaptor with Nikon lens mount. This allows me to put prime lenses on the front of the Canon so that I can get some depth of field. I shot Left Unsaid entirely with that setup. I also own a Nikon D200 with a few lenses. Installed on my Macs are CS4 Master Suite, Final Cut Pro, and some font-management programs but that’s about it really.

Layers: Where did the concept for Black Day to Freedom come from and what was your ultimate goal for the film?

Rob: Way back in 2004, The University of Huddersfield approached me about filming some computer training sessions they were putting on for asylum seekers in the UK. I ran around following these courses and quickly realized there was little point to the film and it was going to end up being a missed opportunity. I proposed that we should talk to the asylum seekers, find out why they were here, and have them write some poems and stories on what had happened to them that made them leave their homes. I then took all this material and collated it into one story, which became Black Day to Freedom. The name came from one of the poems; it’s actually incorrect, as it should be Black Day for Freedom, but as that was what was written on the paper I kept it, as it felt right.

My ultimate goal at the time for the film was to show people what was happening overseas with the whole invasion of Iraq and the mass displacement of people. At the time there was a lot of negative press about asylum seekers taking all the money and housing, but no one really gave much thought to why they were even here. We packaged it all up as a DVD with a book that featured over 30 illustrators and designers worldwide and then sold it online for a short while. The film did pretty well in short film festivals and really helped cement me as a motion designer and short filmmaker. Even to this day when I talk at conferences, this is the most well-received piece out of everything I’ve done. I’m really proud of it!

Layers: Why did you decide to use only After Effects to animate Black Day to Freedom?

Rob: Mainly because I had no other way of achieving the epic scale of the film with any other tool. It was impossible to film something like this, and at that time I had no idea how to even go about doing that. The other reason is that I have absolutely no working knowledge of any 3D program, so I decided to do it in AE, which was a challenge, but I think gives the whole piece a very unique look and tone.

Layers: Could you briefly run us through how the film was created?

Rob: After writing out a rough treatment, we shot friends and ourselves for the characters; in fact, anyone we could get to stand in as a reference. My brother, who is an illustrator, then hand drew each character and created the illustration style. These were then individually scanned and cut out in Photoshop. I created the buildings using textures and line drawings—a bit of a mixture of the two really. Everything was built as a three-dimensional object in After Effects, so if you look at it properly, it’s basically just loads of boxes etc., but it worked out okay by using textures and trying to push AE as far as I could.

I even managed to just about pull off some helicopters! There was one scene where the helicopters are flying above the buildings; it’s a 10-second clip and it took forever to render out because of the complexity of the buildings. In hindsight, I would have created some low-res proxies of the buildings, but at the time I was still learning how to do it and kind of making it up as I went along, so I put the camera really high up and used the full-size buildings, which were something like 6000 pixels high each. Crazy!

Layers: In certain sections of the film, the scene switches to color for a brief second and jumps around. How does this technique, as well as your general use of color throughout, add to the overall impact of the film?

Rob: I came up with that effect by mistake. I had rendered out a clip of the scene with a sky and one without, as I was trying to decide whether to go with a sky or without. I was turning one off revealing the other and back on again and thought that it looked pretty cool. So when the moment of violence really starts to get crazy, this whole glitch-type effect occurs, jolting the viewer momentarily. I think it worked pretty well when combined with the audio dropping out except for the sound of a reporter’s voice. It’s actually my favorite scene in the film and the one people usually ask me about. Throughout the rest of the film, there’s very little color, which is why it works so well, I guess.

Layers: We were very impressed by the use of shadows in the film. Why does a shadow or silhouette of a person sometimes have more impact than the real thing?

Rob: I had some drawings of soldiers but quickly realized that they didn’t come across as powerfully as I wanted. By only seeing the shadow, we’re not led along a path that says this is a soldier from country A or B. We actually don’t know whether these soldiers, if soldiers at all, are here to help or to kill. The scene at the end with the guy with his hands on his head originally had a shadow of a soldier as if he was being captured. I rendered it out and the shadow didn’t appear, and I realized that without the shadow, you’re either looking at a guy who is being arrested or you’re looking at a guy regretting what he has just done. I liked that it was up to the viewer to decide, and more importantly, it actually says more by showing less.

Layers: How do you think digital technology has helped the independent filmmaker?

Rob: I think it’s now so easy to go out there and make a film without any financial backing or support. You can basically just make a film with a phone camera and a laptop these days. These are good times to be a filmmaker.