Don’t Crop My Pictures!

“Crop my picture and you’re a dead man.” That’s what David Page, one of the contributors to my next book, said to me in an email when he submitted one of his pictures for publication. After his demand was a ☺.

Basically, David, a heck of a nice guy and former fine art photographer and teacher at Duke University, was asking, in a nice way, that his image not be cropped. I wrote back, “I’ll crop you later! Only kidding! Real men don’t crop. No worries.” ☺

David’s comment was the inspiration for this column because I agree 100% with his philosophy. To me, and to most of my photographer friends, cropping in-camera and in the digital darkroom is one of the keys to a good image—a good exposure and an interesting subject being among the other key ingredients that make a good photograph.

In fact, when I work with publishers, including my friends at Layers magazine, the only request I have is to please not crop my pictures. It’s a request that surely makes the art director’s job more difficult, and I appreciate their extra effort.

Cropping goes hand in hand with composition, because if you have an expertly composed photograph and then it’s cropped poorly, the composition goes down the tubes, or maybe to Davy Jones’ Locker, according to David Page.

So this issue’s column is all about what’s inside the four borders of a digital image. We’ll begin with image capture, and then move to onscreen cropping.

Basic rules of composition

Here are some things to keep in mind to help you get the best in-camera exposure.

Rule of Thirds: Perhaps the most basic rule of composition is to imagine a tic-tac-toe grid over the image in your viewfinder and to place the main subject where any of the lines intersect. Of course, like all so-called photography rules, this one is meant to be broken. However, it’s a good place to start when it comes to careful composition.

Check out this photograph of a cowgirl and imagine that tic-tac-toe grid over the image. Both the cowgirl and the shadow of a cowboy standing off-camera are placed where lines would intersect.

Place subject off-center: When we take a picture with the subject off-center, we give the viewer the opportunity to unconsciously scan the entire picture for other interesting elements. When we place the subject in the dead center of the frame, the viewer’s eyes get stuck on the subject.

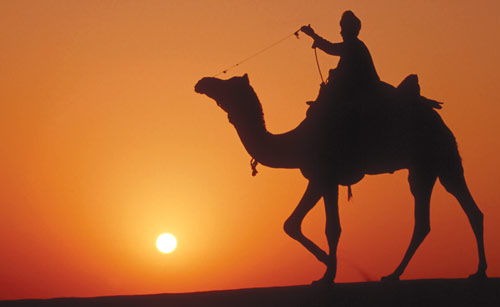

An easy way to remember this rule is to think: Dead center is deadly. That’s what I was thinking about when I took this picture at sunset in Rajasthan, India.

Use a foreground element: Composing a landscape with a foreground element gives the viewer a reference point from which to view the main scene. No foreground element, no reference point. Composing a picture of a person with a foreground element (or surrounding element), which usually means shooting close to the person, makes the picture more personal and intimate.

This picture of a Huli Wigman, whom I photographed in Papua New Guinea, illustrates how using a foreground element, the leaves, can enhance a portrait.

Make the rounds: Before you press the shutter release button, make the rounds. That is, scan the edges of the viewfinder to see if any distracting objects are intruding into your carefully composed image.

Before I took this picture in Namibia, I carefully scanned the frame to make sure no distracting elements (people climbing on the dunes and their footprints) were in the frame.

Basic rules of computer cropping

And here are some things to keep in mind when you’re editing images on your computer.

Crop first: When you open an image on your monitor, there are two reasons why you want to crop first. One is that you can customize your image to exclude unwanted objects and boring areas of a scene, thereby focusing the viewer’s attention on the main subject.

The other is that when you adjust Levels and Curves, areas that are cropped out won’t affect your judgment as to the highlights and shadows in the scene—especially if those cropped-out areas were very dark or very light.

Here’s a before and after pair of images from Antarctica that illustrates creative cropping—along with a few creative enhancements.

Crop to find pictures within pictures: Here’s a fun and creative exercise. Open a picture, and then use creative cropping to find other pictures within a picture. If at first you don’t succeed, try and try again. Keep in mind that in most cases, there’s a good picture within a picture.

I like my original horizontal photograph of this polar bear, which I took in the Subarctic. But after playing around with cropping, I discovered this nice vertical image, which I also like.

After you crop: If you plan to display a print that’s not a standard frame size, you’ll need a custom matte, which you can have cut at a framing store, or a custom frame. Another option is to have your print mounted on foamcore or other mounting material. Online labs such as Mpix.com can help you out in this area. Sure, you’ll have to pay a few more bucks for custom matting, mounting, and framing, but what would you rather have, a picture with impact or a picture with some boring dead space?

This picture of a momma polar bear and her cubs was carefully cropped from a full-frame image to the panorama format. I added the black border, brushed aluminum frame, and drop shadow in Photoshop to simulate a framed image hanging on a wall.

Okay, I’m outta here. I think I’ll start going through my tens of thousands of images to see how a better crop could result in an improved image. In between editing, I’ll check my email for other “dead man” notes.