Aiding Biologists with Wildlife Photography

(Editor’s note: There was a big announcement last week that the greater sage grouse does not need Endangered Species Act protection thanks to land conservation efforts across the western U.S. This seemed like a good time to share this excerpt from Chapter 7 of Moose Peterson’s book, Captured.)

Literally in the Backyard

It’s 8:00 p.m. as I back the truck out of the driveway. There’s not much camera gear loaded—a D3, a couple of lenses, and three flashes. It’s April and there is most definitely a chill in the air, so I have my heavy Nomar jacket and gloves packed. I only have a 15-minute drive to the rendezvous point, most definitely the closet project to home in my career. I arrive at the Green Church 15 minutes early (I want to watch the eastern horizon at sunset—there’s always something in the air). A shooting star lights up the sky and, as it fades, headlights from a vehicle just coming off the highway light up my truck.

It’s an old, faded California Department of Fish & Game (DFG) Game Warden truck that was later described as being held together by duct tape and baling wire. Inside are the biologists I will work with for the next couple of years. The lead biologist, a master’s degree candidate from Idaho State University, has already earned a heck of a reputation. The quiet guy in the back is a Ph.D. candidate from Georgia (the country, not the state) working on black grouse (there’s a bird I want to photograph!). The first thing he says to me after introductions is, “I have your book!”

When my gear is transferred over to their truck, we head down the road. The location we’re heading to is nothing new to me—I’ve been going there since 1989—and the species we’re going to find is no stranger either. But the project is totally new and I’m very excited. In the slight glow of a new quarter moon, the headlights go off, the engine shuts off, and we don our gear. We head through the closed gate and we start what will turn out to be a six-mile walk through the sage in the pitch black darkness of a Sierra night.

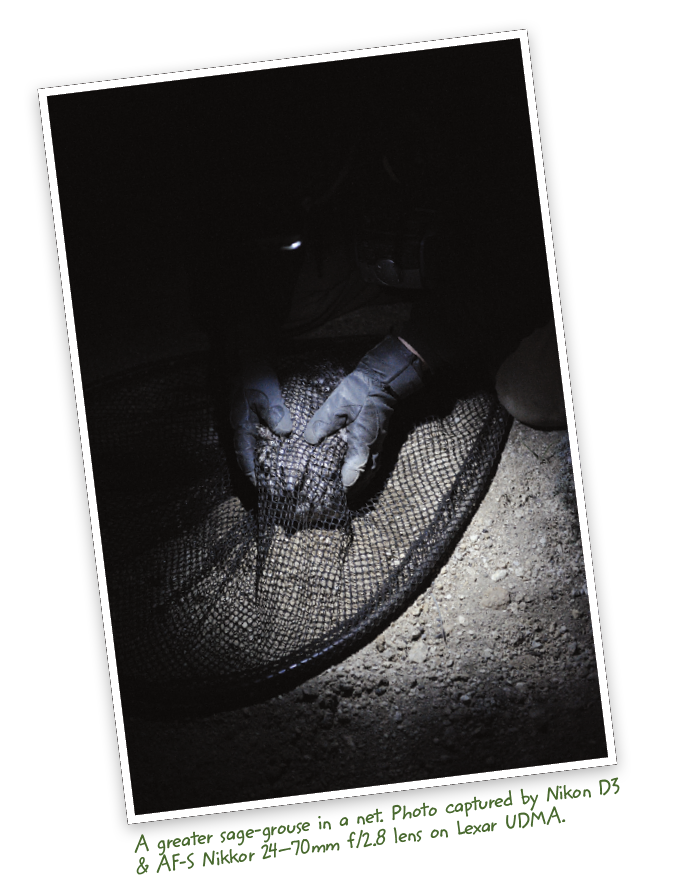

Leif, the lead biologist, did a practice run with his field tech Ben, so I’d know the drill when the time came. While it isn’t new to me, I was new to them, so there is at first some initial shyness with a stranger in the mix. We venture further into the meadow, heading to a known roost area. Then, Leif comes to a halt, points something out to Ben, the boom box comes to life with the recording of an ATV roaring down a trail, and the pace turns into a frantic near-run, as we’re less than 50 meters from the prey. Then, the spotlight quivers. Ben flares right, then left, and back again, making a question mark of a path. Within a heartbeat, the hen is in the net and we’re on the ground next to a greater sage-grouse (GSG).

This project is trying to better understand the survival rate of the GSG young and how they utilize their habitat. My being here was an extension of my own project photographing what many consider an endangered species (though it doesn’t have that designation). I’ve been photographing bits and pieces of the GSG biology since 1989, but hooking up with biologists working on the population on my own doorstep was hard, because no one was doing much other than monitoring. Then came Leif and a whole new opportunity.

The method I just described is how they catch a GSG. In total darkness, the noise and light basically puts the grouse in a trance. With skill, the researcher pretty much just walks up to them and catches them. This technique, called spotlighting, is used on a number of species and has been used on a number of the projects we’ve been a part of. It requires total darkness to work, which means no moonlight. The bright, clear, starry nights of the Sierra are almost too bright without the moon. For this reason, flash can’t be used to document spotlighting, so over the last two decades, I had no images of that technique. This first night out with the biologists, though, I was more excited about the technology than the subject.

When they did their test run to show me how they would go about catching the grouse and where they wanted me to stand during that capture, I shot with the D3 at ISO 6400 to see if, with that new, high ISO, I would get an image. As you can see, I did! At the first conference where Leif presented a paper on his projects illustrated with my images, the image with the biggest impact was the spotlighting—it had never been seen before. This first night out, that was really my main focus, getting the spotlighting on film, and by 2:00 a.m. when we wrapped, I was quite excited to see what I got.

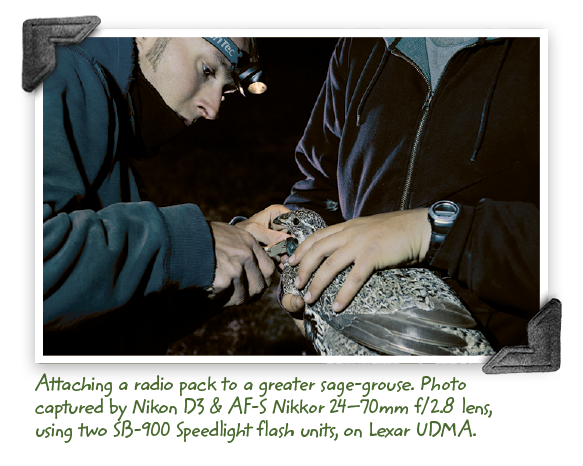

The next night, we did the whole thing all over again. I went through my images from the night before. I decided to shoot ISO 6400 for spotlighting with –1 exposure compensation dialed in the second night. I also went through my images of the biologists processing the captured females. I gelled the SB-900 flashes with a blue gel, because white light at night just doesn’t look right. I thought it was too dark, so I dialed +2/3 exposure comp into the flashes for the second night. I also decided I needed two background flashes rather than one. And I decided to work more with just their headlamps as a light source, letting the inky blackness of night fill in the rest of the photo. The trick was to remember to change the ISO when I turned the flashes on, and change it again when I turned them off.

While walking and looking for the grouse in the dark, I did my usual thing and asked questions. I asked things like, “How much do they weigh?” Leif replied quietly, “Females: 3 lbs. Males: 7 lbs.” After jotting that down, I asked how many chicks they have. “First clutch, up to 10 typically. Second is four to six,” he answered. “How old are the chicks when they fly?” “You ask a lot of questions. They can fly at 14 days, short distances.” The pace quickened and I took that as a sign to be quiet. Leif is a really good guy, a great biologist, and I have a lot of respect for him. And, he answers all my questions.

The locale we were walking is called the Long Valley caldera, the second most active caldera in North America. It has a very gentle slope to it, covered in this funky alkaline grass plant stuff (I know my egetation really well). We were actually walking on a lek, that being the place where the males gather at first light to dance and boom, hoping to attract a female so they can mate (the males having nothing to do with the nesting or rearing process). I was just thinking about that when we all heard the most amazing, haunting, resonating moan come from below our feet. It was really cool!

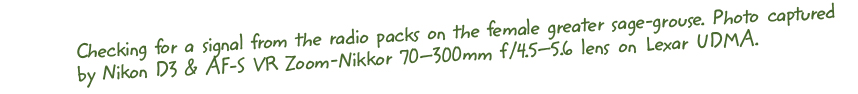

The biologist had captured, marked, and attached radio packs to all the hens he needed for this population, so after the second night, they were done. Then the waiting process began, and much like the Attwater’s prairie chicken project, daily monitoring of the females began to determine who was nesting and the nest locations.

Three weeks later, we were up in the Bodie Hills when the old, green, retired warden’s Bronco stopped with a lurch. The door swung open out of my hand—the truck was pointing down a steep grade. “The road is washed out beyond here. Gotta walk the rest of the way.” I got up at 2:20 a.m., drove 30 minutes to meet up with the biologists, and then drove with them another 40 minutes to get to this point. The sun was a rumor on the horizon when I grabbed my camera gear and headed off while attempting to keep up with the 24-year-old springbuck biologists I was working with. We went down at an alarming rate and speed in the darkness, alarming because we’d have to hike back up the same grade to get back to the truck.

A mile down the grade, the antenna went up and the signal was found. Cross-country we went, hurdling sagebrush in a marathon race with the sun. First down a gully and then up a hill, my guides moved like pronghorn sheep and quickly pulled away from me (oh, to have young legs). Our route was precarious at best, as we zigzagged, following the signal. We reached a rise and got another sounding. I looked over my shoulder to see the road, way below us.

Not even able to catch my breath, we were off again, still cross-country, but now following the ridgeline we had climbed to. The biologists came to a quick halt. The signal had exploded, which meant the quarry was less than 10 meters away. This routine was familiar— we just did it the morning before—so I froze. Spotting the object of our quest, the biologists crouched down, and walked very slowly toward the tan-colored lump at the base of a sage. Less than a meter away, it exploded into the air and down the slope, and the biologists froze. When they stood up and I saw their faces, they looked like they’d just swallowed a lemon.

“There’s none here. Must have been predated upon between 5:00 last night when we last checked and this morning.” “She’s broodless.” With that, we headed cross-country again, at least at a little less feverish pace, and worked our way back to the truck. The three-mile jaunt netted all of us nothing: the biologists weren’t able to collect any data and I didn’t get a photograph. Mother Nature still rules the roost and, for the moment, the greater sage grouse had five less chicks to boost its falling numbers.

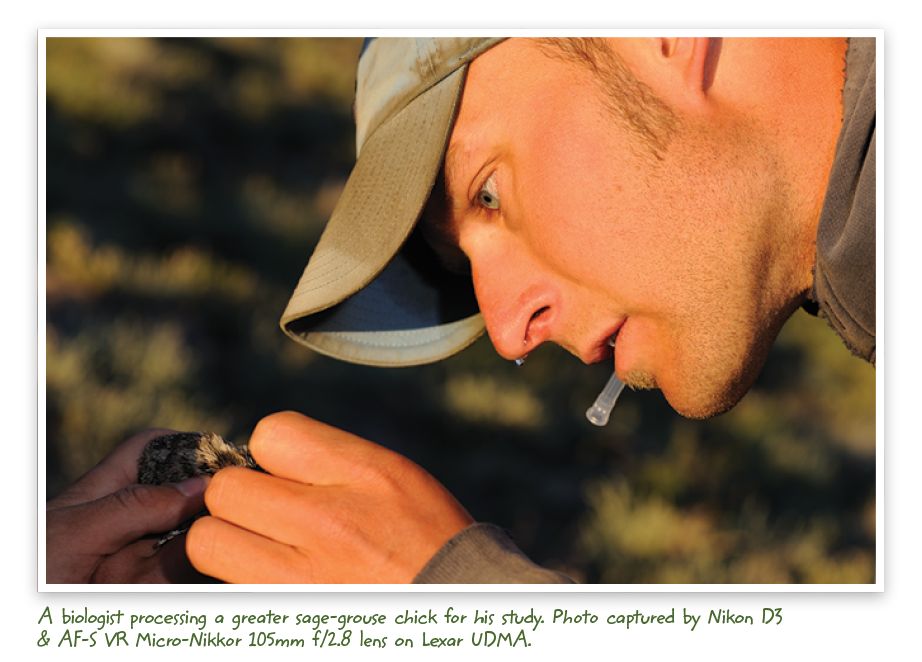

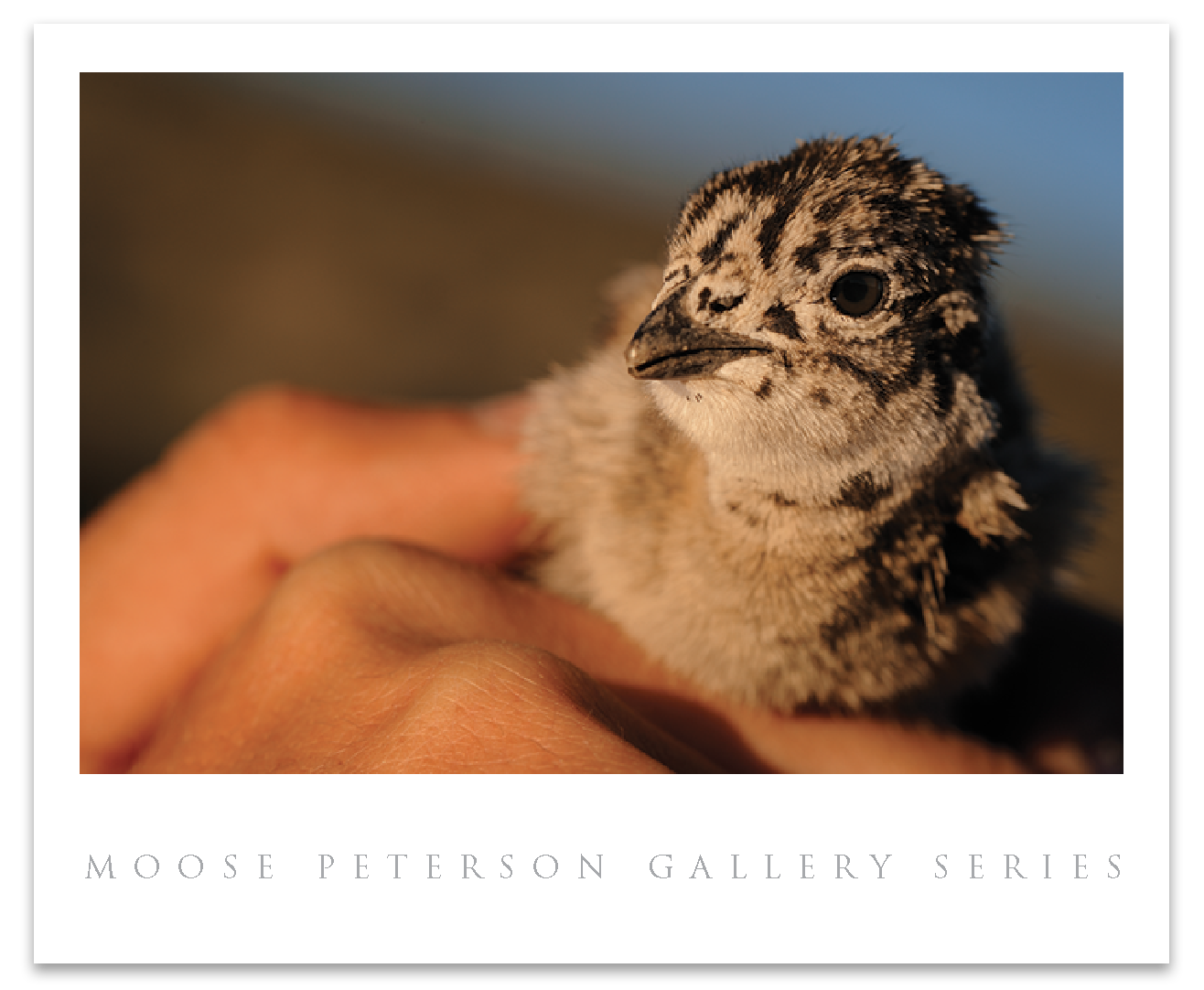

We had done this exact same thing the morning before, with the only difference being the chicks were still present. The hen had gathered them all under her for the night, so they could stay warm. That’s why we had to find them prior to sunup. With them safely gathered up, without saying one single word (which meant I had to ask my questions later), they were processed and released. The hen was just a stone’s throw away, clucking at us as we hurried to move away. That was the whole point of this project: to find out how successful the clutches are, how many chicks make it to the first winter, and how in all of this, the GSG utilizes the habitat in their win-or-lose battle with life.

When they had that four-day-old chick in hand and the first light of day lit it up, the click of the camera meant more than just recording the moment. It was a 20-year quest for me, one more answer for Leif, and a little hope for the species.

One year later, I was at Photoshop World when my iPhone vibrated in my pocket. After the session, I listened to the voice message: “Moose, I have a nest you can photograph. Give me a call!” It was Leif with news I’d waited nearly two decades to hear. I instantly called him back. The nest had only a few days before it hatched out. The day I got home would be the only opportunity to photograph the nest. That afternoon, Leif guided me up the ridge, through the sage, and to a little outcropping of rock. We hadn’t spoken a word since we left the truck. Leif took a new route every time into the nest, so no predator could follow it. He pointed, and there before us was the nest. We could barely make out the hen, staring back at us, holding tight, hoping we wouldn’t come any closer. I made a couple dozen clicks and, minutes later, we were back at the truck.

I’m close, but I don’t have the whole story of the greater sage-grouse yet, on film or paper. It’s one of many projects, all involving biologists, that we are still working on. When will I feel I have finished these projects? When I have fulfilled the quest for knowledge with the answers captured on film.

All photography ©Moose Peterson.

To read more about Moose Peterson’s wildlife photography and work with biologists, and his tips for both, check out his book, Captured: Lessons from Behind the Lens of a Legendary Wildlife Photographer or his online classes for KelbyOne.